In order to engage regularly with members of the local community, The Dyer Island Conservation Trust (DICT) along with partners Marine Dynamic Shark Tours and Dyer Island Cruises hosts Marine Evenings. These evenings are held at their establishment, ‘The Great White House’ in Kleinbaai, and often see over 60 people attending to discuss issues regarding the local marine environment and conservation challenges.

“The role of citizens in scien-ce is often overlooked” says Wilfred Chivell, founder of the DICT and owner of Marine Dynamics and Dyer Island Cruises. “We feel that our community has become our eyes and ears on our surrounding beaches, particularly for marine mammal and bird standings”.

One institution which often connects with the DICT to report sightings is I&J Abalone farm, Danger Point.

VIMS PSAT tag retrieved by Dirkie Kotze Risk coordinator for I&J Danger Point.

VIMS PSAT tag retrieved by Dirkie Kotze Risk coordinator for I&J Danger Point.

On the 13th January 2014, Mr. Dirkie Kotze – Risk Coordinator for I&J, contacted the DICT regarding a device he found washed onshore at their site.

The device was collected by Wilfred, who identified it as a PSAT (Pop-Up Satellite Archival Tag). DICT Biologist Ali-son Towner undertook the task of tracing the origin of this tag along with Mike Meyer from Oceans and Coasts.

PSATs are data loggers used to track the movements of larger migratory marine species. The tag records data over a specific time period, which is then released via active corrosion when the pre programmed time period (determined by the scientific team) ends. The information is transmitted to an overhead satellite every time the tag breaks the water surface and data obtained can vary from location, depth of dives, water temperature and time spent on dives. This information can then be used to better understand the migratory patterns, feeding eco-logy and behaviour of the tagged species.

“These tags are no strangers to the DICT” says Alouise Lynch, Operations Manager at the DICT “Our team of Biologists have deployed them before on Great White Sharks, tracking them as far as Madagascar in less than two months on departing the Greater Dyer Island region”.

Chancellor Professor of Marine Science at VIMS (Virginia Institute of Marine Science), Prof. John E. Graves, responded to Alison’s query and confirmed that the tag was indeed one of theirs, however due to the identity code being damaged he could not confirm the species this tag had been deployed on. The DICT posted the tag to him for analysis. He then sent the tag to the original manufacturer, Microwave Telemetry, to download the data which would contain the ID number of the tag.

VIMS deployed approximately 200 tags, in the Western North Atlantic, with all of them except a handful deployed short term (10, 30 or 50days) to examine post release mortality in fisheries species. There were also tags deployed for longer periods. On the 20th February 2014 Professor Graves sent through the results of the data they retrieved from the PSAT – which were incredible.

VIMS PSAT being deployed onto a Blue Marlin by Dr. Graves and his team.

VIMS PSAT being deployed onto a Blue Marlin by Dr. Graves and his team.

The tag was deployed on a 140kg Blue Marlin on the 1st of November 2008. The tag released 10 days later as programmed, and popped off around 119 km to the east from the point of release.

It then transmitted the archived information for almost 30 days before the battery power ran out, and 85% of the archived data was recovered.

“There is not much we know about the fate of the tag after that time, except that just a little over five years later it mana-ged to wash up near you in South Africa!” said Professor Graves.

The tag collected temperature, pressure (depth), and light level data over the ten day deployment period (archived data), as well as for the time that the it was at the surface transmitting the information to passing satellites (real time). Based on the fact that the Marlin was moving up and down in the water column for the ten days, it was evident that the fish had survived the catch and release. The tag showed apparent day night movements up and down the water column and when released it showed a constant day night real time capture where the tag would have been drifting on the surface of the ocean. The depth data showed that the fish spent the vast majority of its time near the surface, but did make some dives in excess of 100m!

“We have noted cases of predation on the tags (and presumably the fish) on occasion, and sharks are the suspected culprits” continued professor Graves over email.

“When this happens, the day/night signal stays dark until the tag is regurgitated. Sometimes the diving behavior changes dramatically.

Also, as the tag is buffered somewhat from changing temperatures by being inside the animal, one does not see an immediate decrease in temperature on a dive.

For endothermic sharks, such as white sharks or mako sharks that have an elevated body temperature, one does not see a change in internal temperature during a dive (only if they eat something else which cools down the stomach).

Marine mammals could also be potential predators, but they maintain higher body temperatures than the endothermic sharks however there was no indication that this tag had been predated on”.

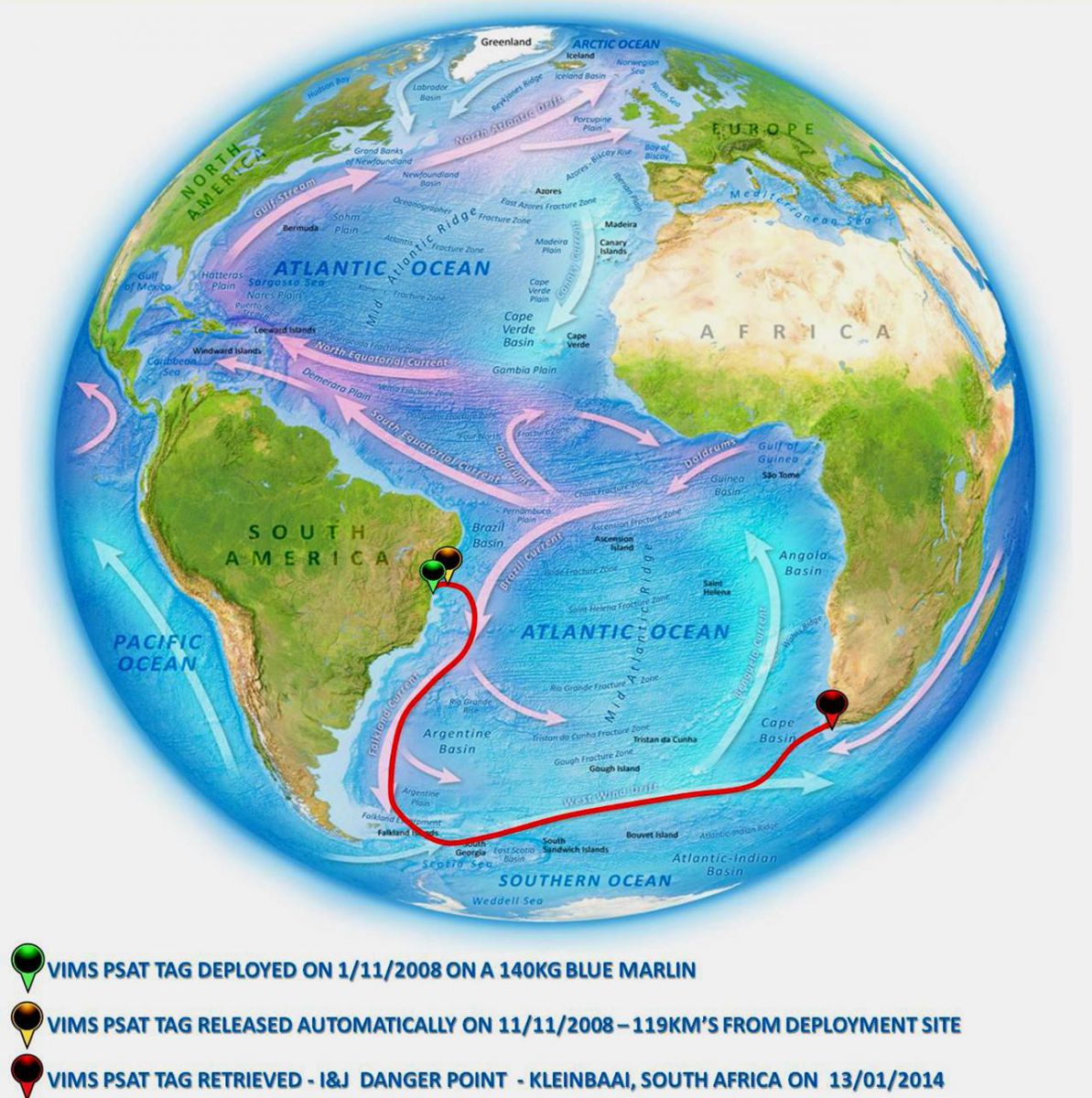

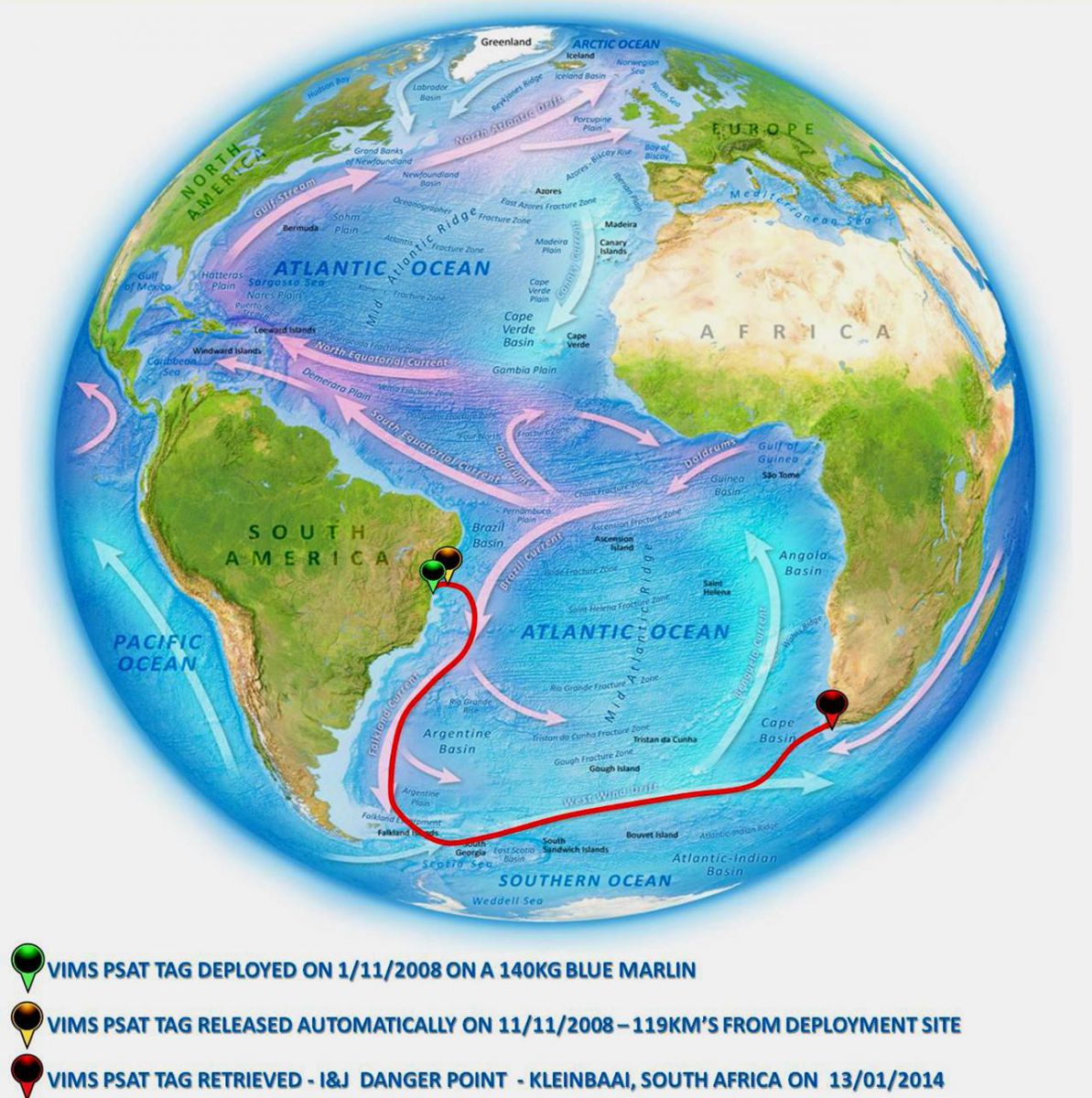

Oceanographic map depicting deployment, release and retrieval of The PSAT found at I&J Danger Point in January 2014.

The coordinates of the tag and release location are plotted on the global map above (Figure 3).

The journey the device made across the entire ocean basin was remarkable from the point where the Marlin was originally captured in the Western Atlantic, to where the tag detached, eventually ending up at the Danger Point coastline, South Africa, 5 years later.

“It is magnificent that a piece of technology the size of your forearm could survive intact, and retain its data, for 5 years in the Atlantic Ocean” said Lynch.

“We are grateful that this tag was reported to us by Dirkie Kotze, which goes to show that our community has become aware of the need to Think Blue.

Many science and conservation projects today are directly reliant on state of the art technology. At the Dyer Island Conservation Trust our days start off driving Volkswagen Blue Motion technology vehicles – the cleanest, most energy efficient vehicles in the VW range – enabling us to connect with people reporting conservation issues, or interesting finds like this PSAT”.

Mr. Kotze’s choice made a difference, by reporting this find to the Dyer Island Conservation Trust his actions enabled them to return the valuable data to the scientists who deployed it, thus revealing this truly remarkable story of a tag that well and truly survived the test of time, rough conditions and a relentless ocean!

For more information on the Dyer Island Conservation Trust, please visit www.dict.org.za

Alouise Lynch, Dyer Island Conservation Trust

VIMS PSAT being deployed onto a Blue Marlin by Dr. Graves and his team.

VIMS PSAT being deployed onto a Blue Marlin by Dr. Graves and his team.