Memory Project: Beira

In landlocked Rhodesia the nearest destination for a seaside holiday was Beira, the second biggest town in Mozambique. My father persuaded my mother that it would be good for all of us to take a two-week break, and that the most affordable and fun way to do this was to go camping.

He was acquainted with a man known as Old Oosthuizen who lived two streets away. An artisan of sorts, he had built a caravan that he was prepared to rent out at a very good price. It had a home-made look about it, the box-like bodywork being of unpainted aluminium. It slept four, had a folding table and two cupboards but no fridge or stove. There was also a side tent.

The distance from Gwelo to Beira was about 700 kilometres, which was too far to travel in a day, considering the state of the roads. Accordingly, we set off at a slow pace in the Ford Zephyr, Oosthuizen’s caravan in tow, intending to stop over in Umtali. We climbed the Christmas Pass outside the town, pulled into a motel and hired a chalet for the night. The area was mountainous and forested, and much greener than the drab countryside around Gwelo.

In the morning after breakfast Alan felt an urgent need to empty his bowels. Finding the toilet occupied, he hurried off into the undergrowth. Unfortunately for him, he chose to go downhill from the chalet and my father happened to catch sight of him squatting in the greenery. His anger was so intense it made me suspect that at times he actually hated his oldest son.

“You are never to do that again, do you hear me?” he told the disgusting bush crapper on his return. “That’s what Natives do; not Europeans.”

It was about 300 km from Umtali to Beira. The road was mostly untarred and in poor condition, making progress slow. At a certain point we had to cross the Pungwe River by pontoon, there being no bridge. The last crossing of the day was at 4 o’clock, which meant we should be there no later than three, in case there was a queue. It was after three when we reached the flood plain known as the Pungwe Flats. My father drove as fast as he dared, but there was a cross wind and Oosthuizen’s caravan was an aerodynamic disaster. At a certain speed it began to swing from side to side in an alarming fashion. An oncoming motorist hooted angrily and shook his fist as he took evasive action.

Fortunately we made it in time for the pontoon, were winched across the river, passed through some tropical forest with monkeys swinging in the trees, and made it to Beira by late afternoon. As we passed a smartly uniformed policeman with long white gloves directing traffic at an intersection, Alan leaned out of the window and shouted, “Caramba! Caramba! Treshertinda yonda scootas! Radioclub da Mozambique!” This was the only ‘Portuguese’ he knew, but from his accent you could have been fooled into thinking he had been born in Lisbon, and not London.

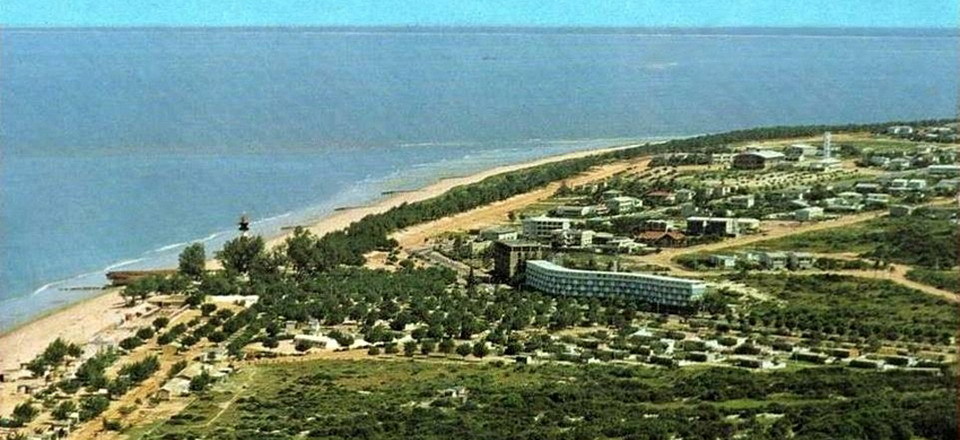

The Estoril Caravan and Camping Resort was situated on the beachfront near the Estoril Hotel. We were allocated a site some distance from the ablution block and Alan and I helped to erect the side tent. Jean, who was about 5 years old, played with her dolls on one of the bunk beds while my mother prepared supper. She heated tinned food on a Primus stove and there was the smell of meths and paraffin as well as cooking. The air was thick and warm, the humidity must have been around 90 percent and everything felt sticky with sea salt. As it grew dark swarms of mosquitoes began to forage for human blood, and we were forced to take refuge inside the caravan behind the mosquito net screens.

The days were hot, the sea was lukewarm and the beach was a dirty brown colour. In that climate and that setting no pleasure could have surpassed the joy of sucking on an ice lolly made from Mazoe citrus concentrate.

On one occasion the camp’s main sewer blocked and a tanker pulled up nearby and a big mobile diesel pump filled it with stinking effluent. Then one evening a car drove slowly up and down with a man in the passenger’s seat leaning out the window shouting into a megaphone. His English was terrible but he managed to convey a message to all campers that they should stay inside while DDT was being sprayed. In due course a truck appeared and then we were engulfed in a dense fog of pesticide that burned in the nose and eyes and seared the throat and lungs. The mosquitoes stayed away for two nights and then returned in even greater numbers.

Our holiday was particularly ill timed from my mother’s perspective. It was after supper a day or two before we were due to pack up and return to Rhodesia. She had gone off to the ablution block and on her return to our cramped little caravan she seemed distressed. She held her toilet bag and towel in front of her but I caught a glimpse of the big red blood stain on her skirt. She murmured to my father that there had been an accident, and when he saw the evidence his reaction was one of exasperation and not sympathy. Not surprisingly she was crying, and between sobs the accusations and recriminations tumbled out. Alan, Jean and I went for a walk to the beach and back.

It was the kind of holiday that left you wondering why you hadn’t rather stayed at home.

To view my longer work as an author, you can find me on Smashwords here.