New Space Weather Network Extends over Africa

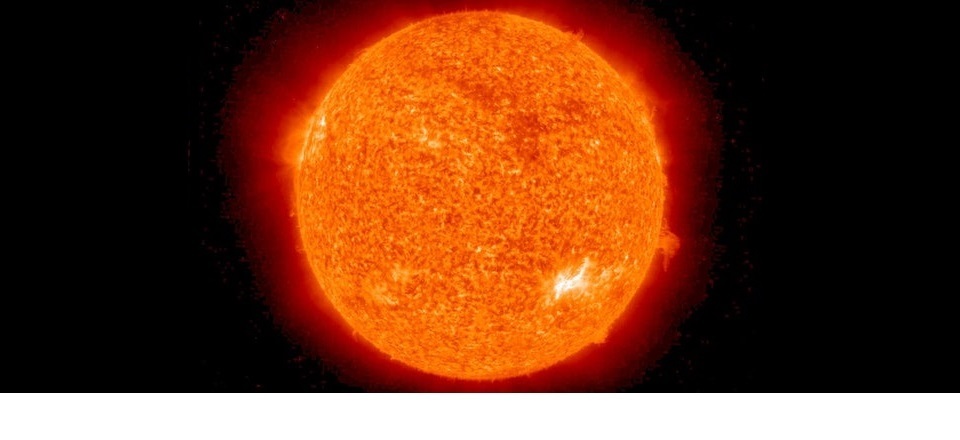

Sensors will monitor solar emissions that threaten GPS and radio signals.

By Sarah Wild |

A new network of dedicated antennas in Africa will lend insight into the havoc that storms of charged particles from the sun wreak on satellite and radio communications. Zambia set up its first such sensor in March - one of eight multifrequency receivers being deployed around the continent, in addition to four already operating in South Africa. Kenya and Nigeria will install their receivers by the end of the year.

Feeding into an upgraded space weather center scheduled to open in South Africa in 2022, the network will provide real-time data on how solar storms distort the ionosphere, the charged outer layer of Earth's atmosphere. This distortion can have dangerous consequences, says Mpho Tshisaphungo, a space weather researcher at the South African National Space Agency (SANSA). Signals between crucial satellites and the ground pass through this region, where charged particles can cause interference. Also, high-frequency radio signals (often used in defense and emergency services communications) have to bounce off the ionosphere; Tshisaphungo notes that when solar storms alter the layer, “the radio signal may either be attenuated, delayed or absorbed by the ionosphere.”

South Africa has already been providing global networks with information about the ionosphere above the country in periodic batches, relying on satellite and ground data from international space weather programs. The new network will give Africa its first access to 24/7 local details on how the sun's behavior is affecting the atmosphere overhead, researchers say.

“While there are international data available, if you want to look at what's happening on the African continent, then you need to take measurements in Africa,” says John Bosco Habarulema, a space scientist at SANSA. Habarulema, researcher Daniel Okoh of Nigeria's National Space Research and Development Agency, and their colleagues developed a model last year that maps electron density in the ionosphere and fills in measurement gaps. (Tshisaphungo is also a co-author.) The new local receivers will boost this model's accuracy and let it describe fluctuations over the full continent.

“We need to have the global perspective and put that [data] into our global models,” says Terry Onsager, a physicist at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Space Weather Prediction Center. “But at the same time, space weather disturbances can vary enormously from location to location.” And it is becoming increasingly important to model the ionosphere's behavior, he says, because “we're getting more and more reliant on technologies that are reliant on space weather.”

This article was originally published with the title "African Skies" in Scientific American 323, 5, 22 (November 2020).

.jpg?width=200&height=94)